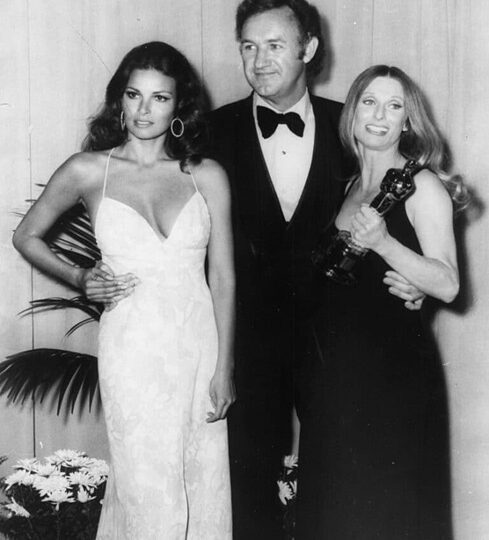

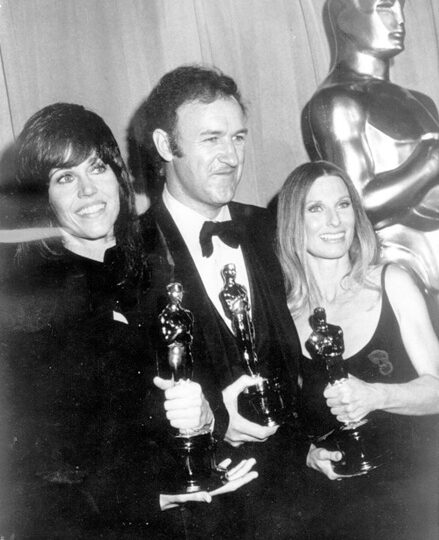

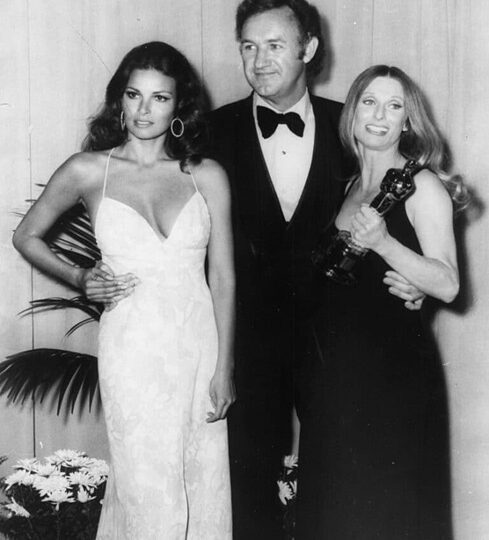

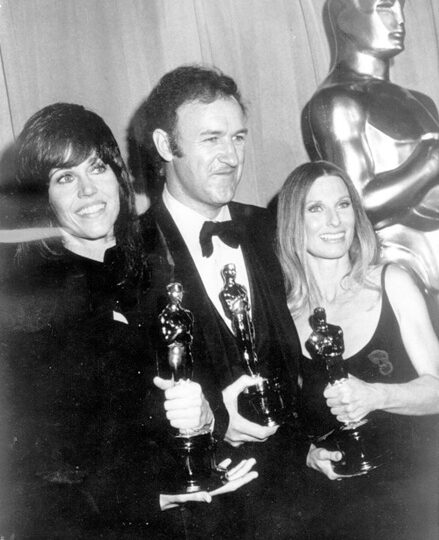

The 1972 Oscars photo you’re seeing is real and untouched — examine it carefully.

The more one looks back at the 1972 Academy Awards, the more the evening feels like a precise snapshot of Hollywood standing at a turning point.

It was a moment when the elegance and rituals of classic studio-era glamour still held their ground, yet a new, rougher.

More confrontational kind of storytelling was already reshaping the industry from the inside. The ceremony was not simply an awards night.

It functioned as a cultural marker—a flash of light capturing an industry in transition, aware of its past but increasingly pulled toward a more restless future.

The 44th Academy Awards, held on April 10, 1972, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, unfolded during a time when American cinema was undergoing a profound transformation.

The old studio system had largely faded, and a generation of filmmakers influenced by European realism, political unrest, and social change was redefining what mainstream Hollywood films could look and feel like.

That shift was visible not just in the winners, but in the overall atmosphere of the night.

The ceremony crowned The French Connection as Best Picture, and that choice alone spoke volumes about the era’s changing appetite.

Directed by William Friedkin, the film rejected polished escapism in favor of raw energy, urban grit, and moral ambiguity.

Its handheld camerawork, location shooting, and relentless pacing made it feel closer to documentary realism than traditional Hollywood crime dramas.

The Academy’s embrace of such a film signaled a growing respect for stories that felt urgent, uncomfortable, and grounded in reality.

The French Connection went on to win five Oscars, including Best Director for Friedkin and Best Actor for Gene Hackman. Hackman’s portrayal of Detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle remains one of the defining performances of the era.

What made the win particularly striking was how little Hackman resembled the classic image of a movie star.

He appeared gruff, unglamorous, and intensely human—a working-class figure driven by obsession rather than charm. His victory felt less like a celebration of celebrity and more like recognition of commitment to craft.

Hackman later reflected on the demanding nature of the production, describing long shoots in harsh winter conditions and the relentless pressure Friedkin placed on the cast.

His comments underscored how different the film was from traditional studio projects. It was physically exhausting, emotionally draining, and creatively challenging—and those qualities were exactly what gave the performance its authenticity.

In hindsight, Hackman’s win feels inevitable, but at the time it represented a clear break from the polished personas that had long dominated Oscar stages.

Looking at the broader field of nominees that year further reveals how fluid the definition of “important cinema” had become.

A Clockwork Orange, directed by Stanley Kubrick, stood as one of the most provocative films ever nominated for Best Picture.

Violent, stylized, and morally unsettling, it divided audiences and critics alike, yet its influence on cinema was undeniable.

Its presence among the nominees suggested that the Academy was willing—at least briefly—to acknowledge films that challenged comfort and convention.

At the same time, Fiddler on the Roof represented the endurance of classic Hollywood craftsmanship.

With its sweeping musical numbers, emotional depth, and traditional storytelling, it reminded audiences that large-scale, heartfelt productions still had the power to move viewers.

Its success showed that innovation and tradition were not mutually exclusive; they were simply coexisting in an increasingly diverse cinematic landscape.

Perhaps the most quietly devastating nominee was The Last Picture Show, directed by Peter Bogdanovich.

Shot in stark black and white, the film captured the slow emotional erosion of a dying Texas town, focusing on loneliness, longing, and the end of innocence.

Its wins for Cloris Leachman and Ben Johnson were especially meaningful.

These were performances built on restraint and authenticity rather than spectacle, reinforcing the idea that subtle, character-driven storytelling could resonate just as powerfully as grand productions.

What also made the 1972 ceremony feel unusually alive was the awareness that it did not exist in isolation from the world beyond the auditorium.

The early 1970s were marked by political unrest, generational conflict, and shifting cultural values. That tension was visible even outside the venue.

Demonstrations reportedly took place during the event, including protests directed at contemporary films like Dirty Harry, which had sparked debate over its portrayal of violence and authority despite not being nominated that year.

These protests served as a reminder that cinema was no longer viewed merely as entertainment—it had become a battleground for ideas.

Inside the ceremony, music played a crucial role in shaping the night’s identity. Isaac Hayes won Best Original Song for “Theme from Shaft,” a landmark moment in Oscar history.

The win carried significance beyond the category itself, symbolizing a broader recognition of Black artists and the influence of soul and funk on American culture.

Hayes’ presence and performance brought a different energy to the ceremony—one that felt modern, assertive, and unmistakably tied to the era’s social changes.

In contrast to today’s tightly managed broadcasts, musical moments during this period often felt transformative rather than supplemental.

They did not simply fill time between awards; they shifted the tone of the evening, briefly turning the ceremony into something closer to a cultural event than an industry function.

Music, film, and social identity intersected in ways that felt immediate and unscripted.

Yet no moment from the 1972 Oscars has endured quite like Charlie Chaplin’s return.

After decades of controversy and self-imposed exile from the United States during the McCarthy era, Chaplin returned to accept an honorary Academy Award.

As he stepped onto the stage, the audience rose to its feet, delivering what is widely regarded as the longest standing ovation in Oscar history, lasting approximately twelve minutes.

The power of that moment lay not in spectacle, but in shared recognition. Chaplin represented the very foundation of cinematic art—silent film, physical comedy, and emotional storytelling that transcended language.

His return was layered with meaning: acknowledgment of artistic legacy, reflection on political regret, and a quiet form of reconciliation.

When Chaplin finally spoke, his words were simple and unpolished, expressing gratitude rather than grandeur. That restraint made the moment even more moving.

For many viewers, Chaplin’s appearance symbolized Hollywood confronting its own past—both its triumphs and its failures.

It was a reminder that the industry, for all its glamour, is shaped by human decisions, fears, and changes in moral perspective.

The ovation was not just for Chaplin the artist, but for what he represented: endurance, creativity, and the complicated relationship between art and politics.

Taken as a whole, the 1972 Academy Awards felt less like a carefully curated brand event and more like a living reflection of an industry in flux.

It celebrated established legends while simultaneously elevating voices that challenged tradition. It allowed space for controversy, experimentation, and sincerity without appearing overly self-conscious.

This balance is perhaps what many people sense is missing from modern ceremonies. It is not that contemporary Hollywood lacks talent or innovation.

Rather, nights like 1972 carried the unmistakable feeling of change happening in real time.

The applause, the discomfort, the bold winners, and the unscripted emotional peaks all suggested that cinema was evolving—and that the Academy, however briefly, was willing to evolve with it.

The 44th Oscars captured an industry acknowledging its roots while stepping into uncertainty with cautious confidence.

That tension—between nostalgia and rebellion, spectacle and sincerity—is what continues to give the 1972 ceremony its lasting resonance.

Decades later, it remains a reminder that the most memorable cultural moments are often those where history, art, and emotion intersect without trying too hard to manufacture significance.

And perhaps that is why the night still echoes. Not because it was perfect, but because it felt honest—an evening where Hollywood revealed itself not as a finished product, but as a conversation still unfolding.

The more one looks back at the 1972 Academy Awards, the more the evening feels like a precise snapshot of Hollywood standing at a turning point.

It was a moment when the elegance and rituals of classic studio-era glamour still held their ground, yet a new, rougher.

More confrontational kind of storytelling was already reshaping the industry from the inside. The ceremony was not simply an awards night.

It functioned as a cultural marker—a flash of light capturing an industry in transition, aware of its past but increasingly pulled toward a more restless future.

The 44th Academy Awards, held on April 10, 1972, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, unfolded during a time when American cinema was undergoing a profound transformation.

The old studio system had largely faded, and a generation of filmmakers influenced by European realism, political unrest, and social change was redefining what mainstream Hollywood films could look and feel like.

That shift was visible not just in the winners, but in the overall atmosphere of the night.

The ceremony crowned The French Connection as Best Picture, and that choice alone spoke volumes about the era’s changing appetite.

Directed by William Friedkin, the film rejected polished escapism in favor of raw energy, urban grit, and moral ambiguity.

Its handheld camerawork, location shooting, and relentless pacing made it feel closer to documentary realism than traditional Hollywood crime dramas.

The Academy’s embrace of such a film signaled a growing respect for stories that felt urgent, uncomfortable, and grounded in reality.

The French Connection went on to win five Oscars, including Best Director for Friedkin and Best Actor for Gene Hackman. Hackman’s portrayal of Detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle remains one of the defining performances of the era.

What made the win particularly striking was how little Hackman resembled the classic image of a movie star.

He appeared gruff, unglamorous, and intensely human—a working-class figure driven by obsession rather than charm. His victory felt less like a celebration of celebrity and more like recognition of commitment to craft.

Hackman later reflected on the demanding nature of the production, describing long shoots in harsh winter conditions and the relentless pressure Friedkin placed on the cast.

His comments underscored how different the film was from traditional studio projects. It was physically exhausting, emotionally draining, and creatively challenging—and those qualities were exactly what gave the performance its authenticity.

In hindsight, Hackman’s win feels inevitable, but at the time it represented a clear break from the polished personas that had long dominated Oscar stages.

Looking at the broader field of nominees that year further reveals how fluid the definition of “important cinema” had become.

A Clockwork Orange, directed by Stanley Kubrick, stood as one of the most provocative films ever nominated for Best Picture.

Violent, stylized, and morally unsettling, it divided audiences and critics alike, yet its influence on cinema was undeniable.

Its presence among the nominees suggested that the Academy was willing—at least briefly—to acknowledge films that challenged comfort and convention.

At the same time, Fiddler on the Roof represented the endurance of classic Hollywood craftsmanship.

With its sweeping musical numbers, emotional depth, and traditional storytelling, it reminded audiences that large-scale, heartfelt productions still had the power to move viewers.

Its success showed that innovation and tradition were not mutually exclusive; they were simply coexisting in an increasingly diverse cinematic landscape.

Perhaps the most quietly devastating nominee was The Last Picture Show, directed by Peter Bogdanovich.

Shot in stark black and white, the film captured the slow emotional erosion of a dying Texas town, focusing on loneliness, longing, and the end of innocence.

Its wins for Cloris Leachman and Ben Johnson were especially meaningful.

These were performances built on restraint and authenticity rather than spectacle, reinforcing the idea that subtle, character-driven storytelling could resonate just as powerfully as grand productions.

What also made the 1972 ceremony feel unusually alive was the awareness that it did not exist in isolation from the world beyond the auditorium.

The early 1970s were marked by political unrest, generational conflict, and shifting cultural values. That tension was visible even outside the venue.

Demonstrations reportedly took place during the event, including protests directed at contemporary films like Dirty Harry, which had sparked debate over its portrayal of violence and authority despite not being nominated that year.

These protests served as a reminder that cinema was no longer viewed merely as entertainment—it had become a battleground for ideas.

Inside the ceremony, music played a crucial role in shaping the night’s identity. Isaac Hayes won Best Original Song for “Theme from Shaft,” a landmark moment in Oscar history.

The win carried significance beyond the category itself, symbolizing a broader recognition of Black artists and the influence of soul and funk on American culture.

Hayes’ presence and performance brought a different energy to the ceremony—one that felt modern, assertive, and unmistakably tied to the era’s social changes.

In contrast to today’s tightly managed broadcasts, musical moments during this period often felt transformative rather than supplemental.

They did not simply fill time between awards; they shifted the tone of the evening, briefly turning the ceremony into something closer to a cultural event than an industry function.

Music, film, and social identity intersected in ways that felt immediate and unscripted.

Yet no moment from the 1972 Oscars has endured quite like Charlie Chaplin’s return.

After decades of controversy and self-imposed exile from the United States during the McCarthy era, Chaplin returned to accept an honorary Academy Award.

As he stepped onto the stage, the audience rose to its feet, delivering what is widely regarded as the longest standing ovation in Oscar history, lasting approximately twelve minutes.

The power of that moment lay not in spectacle, but in shared recognition. Chaplin represented the very foundation of cinematic art—silent film, physical comedy, and emotional storytelling that transcended language.

His return was layered with meaning: acknowledgment of artistic legacy, reflection on political regret, and a quiet form of reconciliation.

When Chaplin finally spoke, his words were simple and unpolished, expressing gratitude rather than grandeur. That restraint made the moment even more moving.

For many viewers, Chaplin’s appearance symbolized Hollywood confronting its own past—both its triumphs and its failures.

It was a reminder that the industry, for all its glamour, is shaped by human decisions, fears, and changes in moral perspective.

The ovation was not just for Chaplin the artist, but for what he represented: endurance, creativity, and the complicated relationship between art and politics.

Taken as a whole, the 1972 Academy Awards felt less like a carefully curated brand event and more like a living reflection of an industry in flux.

It celebrated established legends while simultaneously elevating voices that challenged tradition. It allowed space for controversy, experimentation, and sincerity without appearing overly self-conscious.

This balance is perhaps what many people sense is missing from modern ceremonies. It is not that contemporary Hollywood lacks talent or innovation.

Rather, nights like 1972 carried the unmistakable feeling of change happening in real time.

The applause, the discomfort, the bold winners, and the unscripted emotional peaks all suggested that cinema was evolving—and that the Academy, however briefly, was willing to evolve with it.

The 44th Oscars captured an industry acknowledging its roots while stepping into uncertainty with cautious confidence.

That tension—between nostalgia and rebellion, spectacle and sincerity—is what continues to give the 1972 ceremony its lasting resonance.

Decades later, it remains a reminder that the most memorable cultural moments are often those where history, art, and emotion intersect without trying too hard to manufacture significance.

And perhaps that is why the night still echoes. Not because it was perfect, but because it felt honest—an evening where Hollywood revealed itself not as a finished product, but as a conversation still unfolding.