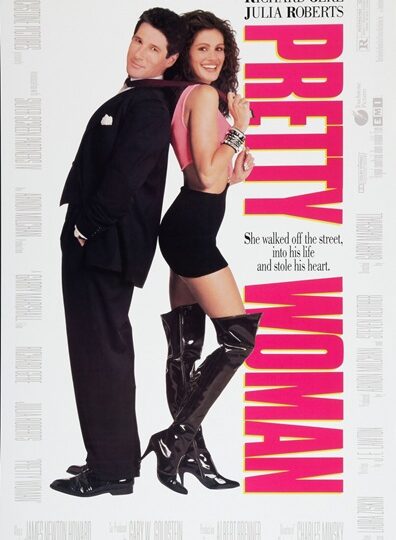

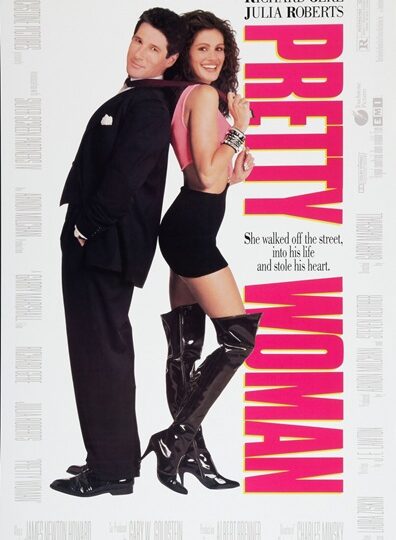

When Pretty Woman was released in 1990, it didn’t just become one of the defining romantic comedies of its era.

It reshaped Hollywood’s approach to fairy‑tale romance for decades to come.

But the film as we know it today — a feel‑good, modern Cinderella story starring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere — was very nearly something completely different.

What began as a much darker, grittier screenplay evolved into a blockbuster classic only after major studios got involved and shifted both tone and direction.

From Dark Drama to Fairy Tale: The Early Script

Long before Vivian Ward and Edward Lewis ever stepped onto a Beverly Hills street, the movie that would become Pretty Woman was titled Three Thousand, named for the amount of money the wealthy businessman agrees to pay a sex worker to accompany him for a week.

That title, simple and stark, reflected the film’s original intent: to be a gritty, socially honest drama about inequality, exploitation, and the psychological distance between classes in 1980s Los Angeles.

The screenplay was written by J.F. Lawton, who envisioned the story in a much harsher light — Vivian’s character was originally drug‑addicted, angry, foul‑mouthed, and far from the polished romantic lead audiences would later embrace.

Lawton later described the early script as bleak and emotionally raw, with a narrative more about economic imbalance than about love or transformation.

In the original ending, Vivian and her friend Kit would be riding a bus to Disneyland, with Vivian staring ahead in despair, disillusioned by her treatment and the world around her.

For years, Three Thousand circulated in Hollywood, admired for its sharp voice but never quite finding a home — until Disney became involved.

When representatives for Walt Disney Studios — specifically the head of their Touchstone Pictures division — saw the script, they saw potential for something very different:

a romantic comedy built on opposites‑attract chemistry, a story that could balance sophistication, humor, and character growth.

With Disney’s backing and a revised screenplay directed by Garry Marshall, the narrative shifted dramatically away from Lawton’s original concept and toward the fairy‑tale romance that audiences now cherish.

The title Three Thousand was ultimately dropped — Disney executives felt it sounded too much like science fiction and didn’t capture the heart of the story they wanted to tell — and the new title was inspired by the lyric and spirit of Roy Orbison’s song “Oh, Pretty Woman,” giving the film both instant cultural resonance and brand recognition.

Casting the Movie: Chemistry, Convincing, and Nearly Different Leads

The casting process for Pretty Woman is now part of Hollywood lore.

Although Julia Roberts and Richard Gere became inseparable from their roles as Vivian and Edward, both actors initially had doubts.

Julia Roberts: A Rising Star Finds Her Breakthrough

At the time she was cast, Roberts was already turning heads for her breakout performance in Mystic Pizza (1988), but she wasn’t yet a household name.

What she was absolutely certain of, however, was one boundary she would not cross: she refused to appear nude in the film — a condition she made clear before filming began and which was respected throughout production.

Richard Gere: Stalled at the Starting Line

Richard Gere, already known for earlier roles like American Gigolo and An Officer and a Gentleman, was hesitant about the role of Edward Lewis.

At first, he didn’t see the character’s depth and felt it was just “a suit and a good haircut.”

But after meeting with Roberts and director Garry Marshall — in part because Roberts wrote him a simple note saying “please say yes” — he agreed to take the part, ultimately creating one of his most memorable performances.

Other big names were considered for the role of Edward before Gere came onboard.

Actors like John Travolta, Christopher Reeve, Kevin Kline, Denzel Washington, and even Sylvester Stallone were at one point discussed, and director Marshall originally envisioned Al Pacino opposite Michelle Pfeiffer.

Pacino later declined and praised Roberts’s performance, acknowledging her undeniable talent.

Continuity Quirks & Set Secrets: Behind the Scenes

Even a carefully crafted film like Pretty Woman isn’t immune to bloopers and continuity quirks — and some of these have become legendary among fans.

The Croissant‑to‑Pancake Switch

One of the most famous continuity errors in the film occurs during a hotel breakfast scene.

In one shot, Vivian is eating a croissant, but in the next, the pastry has magically changed into a pancake — with no narrative explanation.

This happens because the director preferred one take where Roberts ate a pancake rather than the croissant originally featured, even though the editing didn’t sync the food perfectly between cuts.

It’s a small mistake, but it’s become one of the most talked‑about movie bloopers of all time.

Edward’s Changing Tie

Sharp‑eyed viewers might also notice that Edward’s tie changes style and knot from scene to scene — a classic wardrobe continuity issue that didn’t get fully caught during editing.

These tiny inconsistencies don’t detract from the story, but they certainly give eagle‑eyed viewers something to smile about.

Wardrobe That Tells a Story: Costume Design by Marilyn Vance

A huge part of Pretty Woman’s lasting appeal lies in its wardrobe, which serves not just as fashion but as storytelling.

Costume designer Marilyn Vance — who had already established a reputation in Hollywood — was instrumental in crafting Vivian’s look throughout the film.

She designed nearly all of Roberts’ costumes and helped visually define the character’s transformation from streetwear to polished elegance.

The Iconic Red Opera Dress

Perhaps the most legendary outfit in the film is the off‑the‑shoulder red gown Vivian wears to the opera.

Although the studio originally wanted a black dress (presumably for contrast and classic elegance), Vance insisted on red to better complement Roberts’s vibrant presence and the emotional arc of the scene.

After multiple tests, the scarlet gown was chosen, and it has since become one of the most iconic movie dresses of all time, cited by fashion historians and publications as symbolizing Vivian’s transformation and confidence.

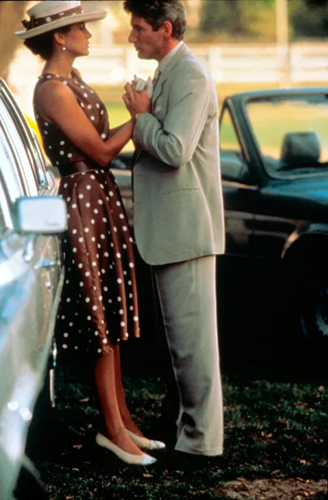

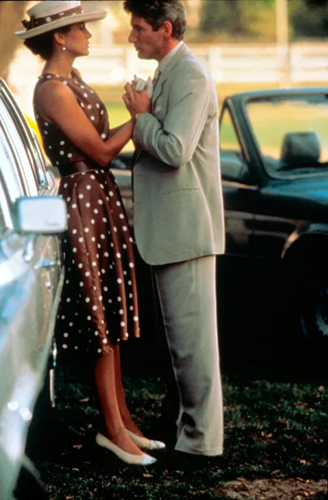

Polka Dots, Polo, and Everyday Chic

Beyond the opera scene, Vance also created some of the film’s most memorable casual wardrobe moments, like Vivian’s brown‑and‑white polka‑dot dress worn at the polo match — built from vintage silk — and the casual yet sophisticated outfits she wears in everyday scenes.

Each piece helps chart Vivian’s evolution from outsider to romantic lead with increasing ease in Edward’s world.

Edward’s Timeless Suits

Meanwhile, Richard Gere’s wardrobe was designed to reflect Edward’s rigid, polished world.

From tailored Italian suits to refined shirts and ties, his clothing reinforces his character’s control, structure, and corporate success.

Oddly enough, one of those ties, purchased from a modest Los Angeles shop for about $48, became a minor point of continuity trivia when viewers later noticed it seemed to change knots between scenes.

Unscripted Magic: Improvised Moments That Lasted

Some of Pretty Woman’s most cherished moments weren’t scripted — they were born out of playfulness and improvisation.

One memorable example is the jewelry box scene. When Edward presents Vivian with a stunning ruby and diamond necklace before their opera night, he snaps the box shut on her fingers.

That snap was not in the original script — it was an unplanned move by Richard Gere meant to elicit a genuine reaction.

Julia Roberts burst out laughing, and director Garry Marshall kept it in, turning it into one of the film’s most quoted scenes.

In another playful moment during the bubble bath scene, Julia Roberts surfaced after submerging her head under bubbles only to find that the cast, crew, and Richard Gere had momentarily disappeared — a prank that made the final cut and added to the scene’s spontaneous charm.

Gere even performed the piano piece his character plays during a pivotal scene; the melody isn’t just mimed — he actually plays it, showcasing a hidden musical talent that adds real texture to the moment.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

By the time Pretty Woman hit theaters in 1990, it had been transformed from a stark social drama into a warm romantic comedy that spoke to audiences across the world.

The movie grossed millions and helped turn Julia Roberts into a global star while reaffirming Richard Gere’s status as a leading man.

Over the years, the film’s blend of humor, heart, fashion, and fairy‑tale romance has made it a cultural touchstone.

Its story of an unlikely romantic connection — transcending class, background, and expectation — has influenced countless other films in the genre.

The wardrobe, particularly Vivian’s iconic dresses, has sparked fashion retrospectives, exhibitions, and even museum features.

Today, Pretty Woman remains beloved not just as a romantic comedy, but as a story about human connection, transformation, and the magic of unexpected love.

Even decades later, audiences continue to discover it, discuss it, and delight in its quirks — from wardrobe trivia to croissant‑turned‑pancake bloopers — proving that even a classic can be full of delightful surprises.

When Pretty Woman was released in 1990, it didn’t just become one of the defining romantic comedies of its era.

It reshaped Hollywood’s approach to fairy‑tale romance for decades to come.

But the film as we know it today — a feel‑good, modern Cinderella story starring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere — was very nearly something completely different.

What began as a much darker, grittier screenplay evolved into a blockbuster classic only after major studios got involved and shifted both tone and direction.

From Dark Drama to Fairy Tale: The Early Script

Long before Vivian Ward and Edward Lewis ever stepped onto a Beverly Hills street, the movie that would become Pretty Woman was titled Three Thousand, named for the amount of money the wealthy businessman agrees to pay a sex worker to accompany him for a week.

That title, simple and stark, reflected the film’s original intent: to be a gritty, socially honest drama about inequality, exploitation, and the psychological distance between classes in 1980s Los Angeles.

The screenplay was written by J.F. Lawton, who envisioned the story in a much harsher light — Vivian’s character was originally drug‑addicted, angry, foul‑mouthed, and far from the polished romantic lead audiences would later embrace.

Lawton later described the early script as bleak and emotionally raw, with a narrative more about economic imbalance than about love or transformation.

In the original ending, Vivian and her friend Kit would be riding a bus to Disneyland, with Vivian staring ahead in despair, disillusioned by her treatment and the world around her.

For years, Three Thousand circulated in Hollywood, admired for its sharp voice but never quite finding a home — until Disney became involved.

When representatives for Walt Disney Studios — specifically the head of their Touchstone Pictures division — saw the script, they saw potential for something very different:

a romantic comedy built on opposites‑attract chemistry, a story that could balance sophistication, humor, and character growth.

With Disney’s backing and a revised screenplay directed by Garry Marshall, the narrative shifted dramatically away from Lawton’s original concept and toward the fairy‑tale romance that audiences now cherish.

The title Three Thousand was ultimately dropped — Disney executives felt it sounded too much like science fiction and didn’t capture the heart of the story they wanted to tell — and the new title was inspired by the lyric and spirit of Roy Orbison’s song “Oh, Pretty Woman,” giving the film both instant cultural resonance and brand recognition.

Casting the Movie: Chemistry, Convincing, and Nearly Different Leads

The casting process for Pretty Woman is now part of Hollywood lore.

Although Julia Roberts and Richard Gere became inseparable from their roles as Vivian and Edward, both actors initially had doubts.

Julia Roberts: A Rising Star Finds Her Breakthrough

At the time she was cast, Roberts was already turning heads for her breakout performance in Mystic Pizza (1988), but she wasn’t yet a household name.

What she was absolutely certain of, however, was one boundary she would not cross: she refused to appear nude in the film — a condition she made clear before filming began and which was respected throughout production.

Richard Gere: Stalled at the Starting Line

Richard Gere, already known for earlier roles like American Gigolo and An Officer and a Gentleman, was hesitant about the role of Edward Lewis.

At first, he didn’t see the character’s depth and felt it was just “a suit and a good haircut.”

But after meeting with Roberts and director Garry Marshall — in part because Roberts wrote him a simple note saying “please say yes” — he agreed to take the part, ultimately creating one of his most memorable performances.

Other big names were considered for the role of Edward before Gere came onboard.

Actors like John Travolta, Christopher Reeve, Kevin Kline, Denzel Washington, and even Sylvester Stallone were at one point discussed, and director Marshall originally envisioned Al Pacino opposite Michelle Pfeiffer.

Pacino later declined and praised Roberts’s performance, acknowledging her undeniable talent.

Continuity Quirks & Set Secrets: Behind the Scenes

Even a carefully crafted film like Pretty Woman isn’t immune to bloopers and continuity quirks — and some of these have become legendary among fans.

The Croissant‑to‑Pancake Switch

One of the most famous continuity errors in the film occurs during a hotel breakfast scene.

In one shot, Vivian is eating a croissant, but in the next, the pastry has magically changed into a pancake — with no narrative explanation.

This happens because the director preferred one take where Roberts ate a pancake rather than the croissant originally featured, even though the editing didn’t sync the food perfectly between cuts.

It’s a small mistake, but it’s become one of the most talked‑about movie bloopers of all time.

Edward’s Changing Tie

Sharp‑eyed viewers might also notice that Edward’s tie changes style and knot from scene to scene — a classic wardrobe continuity issue that didn’t get fully caught during editing.

These tiny inconsistencies don’t detract from the story, but they certainly give eagle‑eyed viewers something to smile about.

Wardrobe That Tells a Story: Costume Design by Marilyn Vance

A huge part of Pretty Woman’s lasting appeal lies in its wardrobe, which serves not just as fashion but as storytelling.

Costume designer Marilyn Vance — who had already established a reputation in Hollywood — was instrumental in crafting Vivian’s look throughout the film.

She designed nearly all of Roberts’ costumes and helped visually define the character’s transformation from streetwear to polished elegance.

The Iconic Red Opera Dress

Perhaps the most legendary outfit in the film is the off‑the‑shoulder red gown Vivian wears to the opera.

Although the studio originally wanted a black dress (presumably for contrast and classic elegance), Vance insisted on red to better complement Roberts’s vibrant presence and the emotional arc of the scene.

After multiple tests, the scarlet gown was chosen, and it has since become one of the most iconic movie dresses of all time, cited by fashion historians and publications as symbolizing Vivian’s transformation and confidence.

Polka Dots, Polo, and Everyday Chic

Beyond the opera scene, Vance also created some of the film’s most memorable casual wardrobe moments, like Vivian’s brown‑and‑white polka‑dot dress worn at the polo match — built from vintage silk — and the casual yet sophisticated outfits she wears in everyday scenes.

Each piece helps chart Vivian’s evolution from outsider to romantic lead with increasing ease in Edward’s world.

Edward’s Timeless Suits

Meanwhile, Richard Gere’s wardrobe was designed to reflect Edward’s rigid, polished world.

From tailored Italian suits to refined shirts and ties, his clothing reinforces his character’s control, structure, and corporate success.

Oddly enough, one of those ties, purchased from a modest Los Angeles shop for about $48, became a minor point of continuity trivia when viewers later noticed it seemed to change knots between scenes.

Unscripted Magic: Improvised Moments That Lasted

Some of Pretty Woman’s most cherished moments weren’t scripted — they were born out of playfulness and improvisation.

One memorable example is the jewelry box scene. When Edward presents Vivian with a stunning ruby and diamond necklace before their opera night, he snaps the box shut on her fingers.

That snap was not in the original script — it was an unplanned move by Richard Gere meant to elicit a genuine reaction.

Julia Roberts burst out laughing, and director Garry Marshall kept it in, turning it into one of the film’s most quoted scenes.

In another playful moment during the bubble bath scene, Julia Roberts surfaced after submerging her head under bubbles only to find that the cast, crew, and Richard Gere had momentarily disappeared — a prank that made the final cut and added to the scene’s spontaneous charm.

Gere even performed the piano piece his character plays during a pivotal scene; the melody isn’t just mimed — he actually plays it, showcasing a hidden musical talent that adds real texture to the moment.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

By the time Pretty Woman hit theaters in 1990, it had been transformed from a stark social drama into a warm romantic comedy that spoke to audiences across the world.

The movie grossed millions and helped turn Julia Roberts into a global star while reaffirming Richard Gere’s status as a leading man.

Over the years, the film’s blend of humor, heart, fashion, and fairy‑tale romance has made it a cultural touchstone.

Its story of an unlikely romantic connection — transcending class, background, and expectation — has influenced countless other films in the genre.

The wardrobe, particularly Vivian’s iconic dresses, has sparked fashion retrospectives, exhibitions, and even museum features.

Today, Pretty Woman remains beloved not just as a romantic comedy, but as a story about human connection, transformation, and the magic of unexpected love.

Even decades later, audiences continue to discover it, discuss it, and delight in its quirks — from wardrobe trivia to croissant‑turned‑pancake bloopers — proving that even a classic can be full of delightful surprises.