“George… it can’t be you.”

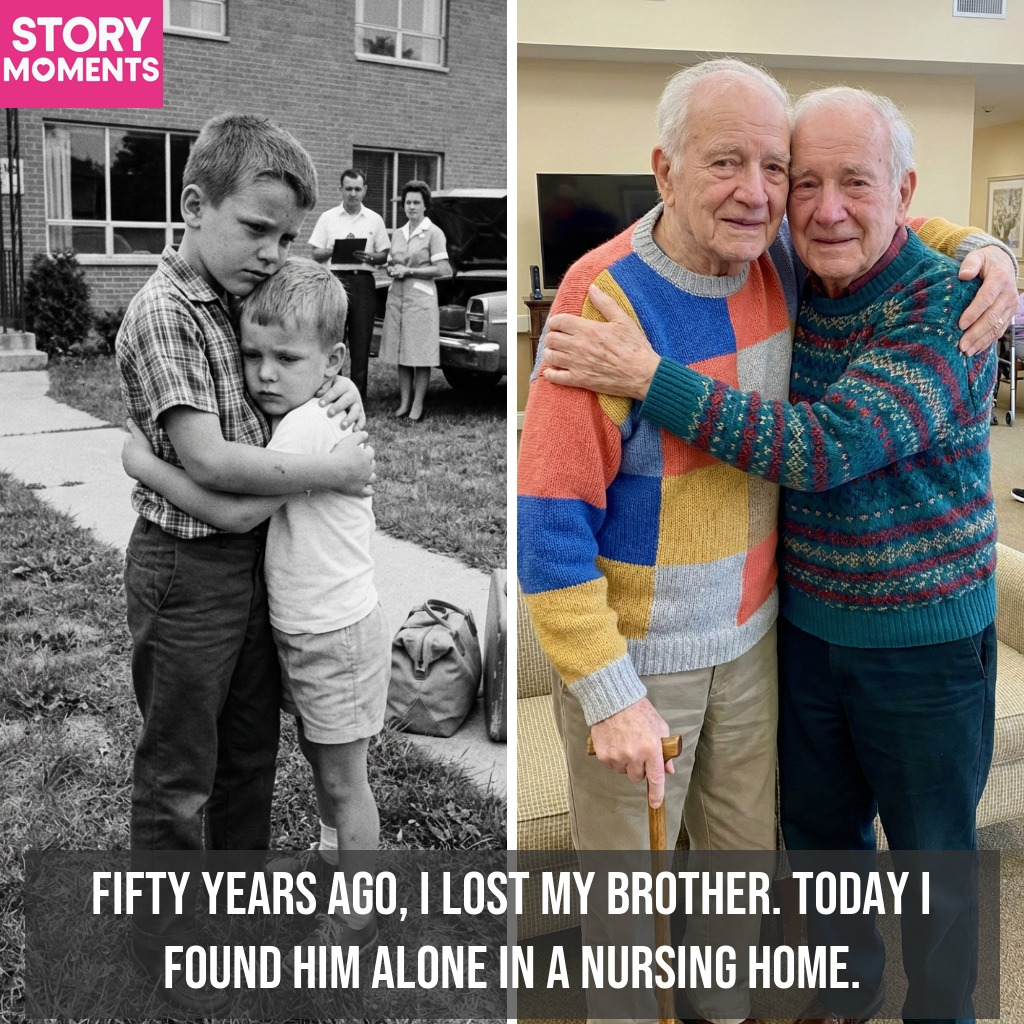

He said it the moment I stepped into the room, before the nurse even finished pushing my wheelchair over the threshold. His voice was thinner than I remembered, frayed around the edges by age and illness, but it was unmistakably his. I hadn’t heard Tommy speak since 1960. Back then, his voice still broke on certain words. Back then, he was four, and I was eight, and the world was about to decide we didn’t belong together.

I couldn’t speak at first. My chest tightened in a way the stroke therapists never warned me about.

“It’s me,” I finally said. “It’s George.”

He laughed then, a soft, broken sound that turned into something dangerously close to a sob. “I knew it,” he whispered. “I knew it was you the second they said your name.”

Sixty-five years collapsed into that moment.

When our mother died, the house went quiet in a way that scared me more than the shouting ever had. She’d been sick for a while, though no one explained much to us. One morning she just didn’t wake up, and by that afternoon there were strangers in the living room speaking in low voices, writing things down, deciding our future with the calm efficiency of people who would go home to dinner afterward.

They said there wasn’t room to keep siblings together. They said it like it was weather—unfortunate, unavoidable.

A family from two counties over wanted one child. One. I was older, easier, they said. Tommy clung to my coat while they filled out the paperwork. I remember kneeling in front of him, promising I’d come back for him, even though I didn’t know how or when. I remember his face twisted with fear as they pulled me toward the door.

He cried my name until the sound disappeared behind the closing walls.

The family who took me were decent enough. They fed me, clothed me, sent me to school. They never hurt me, but they never asked about Tommy either. After a while, I learned not to bring him up. You don’t press on wounds people pretend aren’t there.

When I turned eighteen, I asked about my brother. The adoption records were already a mess. Names misspelled. Dates missing. Offices redirected me to other offices. “No information,” they said. “No trail.”

I tried again in my thirties. Then again after my own kids were born. Every attempt ended the same way: apologies, shrugs, closed doors. Somewhere along the line, Tommy became a ghost—someone I was sure had existed, but who left no proof behind.

I never stopped thinking about him.

Tommy, I learned later, grew up in care. One home, then another, then another. Some were kind. Some weren’t. He learned early not to expect permanence. He worked factory jobs most of his life—long shifts, loud machines, hands roughened by repetition. He never married. “Didn’t seem built for staying,” he told me once, with a small shrug.

He assumed I forgot him.

“I figured you got picked because you were better,” he said quietly, sitting across from me in his nursing home room. “Smarter. Easier. I thought you just… moved on.”

“I looked for you,” I told him. “For decades.”

He nodded slowly, as if filing that truth somewhere safe. “I know that now.”

The stroke came without warning. One minute I was arguing with my daughter about whether I needed help around the house, the next I was waking up unable to move my right side properly. The doctors were optimistic, but the word facility started appearing in conversations more often than I liked.

That’s how I ended up there.

Months later—pure coincidence, the staff said—another man was transferred in. Same nursing home. Different wing. Same hallway.

It was a nurse who noticed the similarities first. Two brothers, both separated by the county. Same mother’s name. Same year. The staff compared our stories the way people do when they sense something extraordinary might be hiding in plain sight.

One afternoon, they wheeled me down the hall.

When Tommy said my name, something inside me unlocked.

We talked for hours that day, and for many days after. We filled in gaps, corrected memories, laughed at how different our lives had been and how strangely similar they felt anyway. We mourned the years that had been stolen from us, though neither of us said it outright. There was no anger left—just a deep, aching tenderness.

Sometimes we sat in silence, watching the light shift across the floor. Sometimes he’d fall asleep mid-sentence, and I’d sit there, listening to his breathing, grateful for something as ordinary as that.

“Funny,” he said once. “All that time, all those miles. And we end up on the same hallway.”

I smiled. “Guess we were harder to separate than they thought.”

When he reached for my hand, his grip was weak, but it was enough.

Fifty years of distance disappeared in one breath—and this time, no one was there to pull us apart.