Fame never saved him. It never protected him.

In many ways, it haunted him — or, at least, it echoed across decades of a life spent walking the razor’s edge between visibility and obscurity.

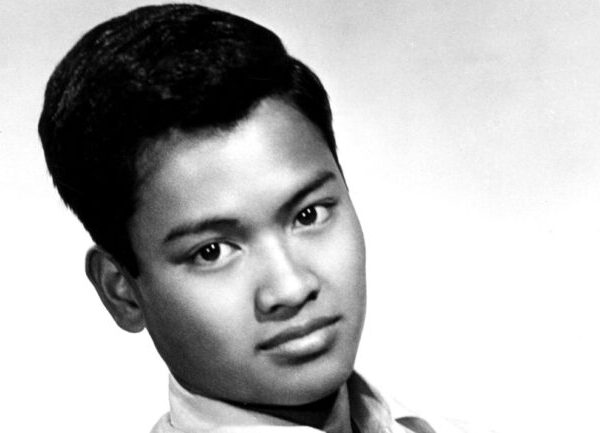

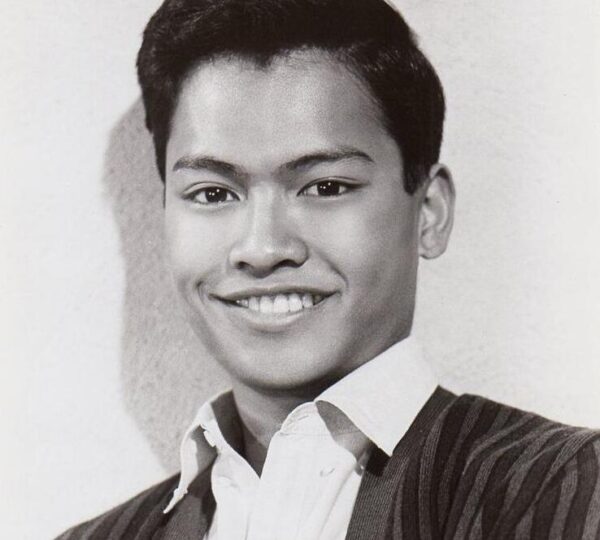

But the quiet truth about Patrick Robert Adiarte is that he made a mark deeper than most would ever know, even if his name was not always on the marquee.

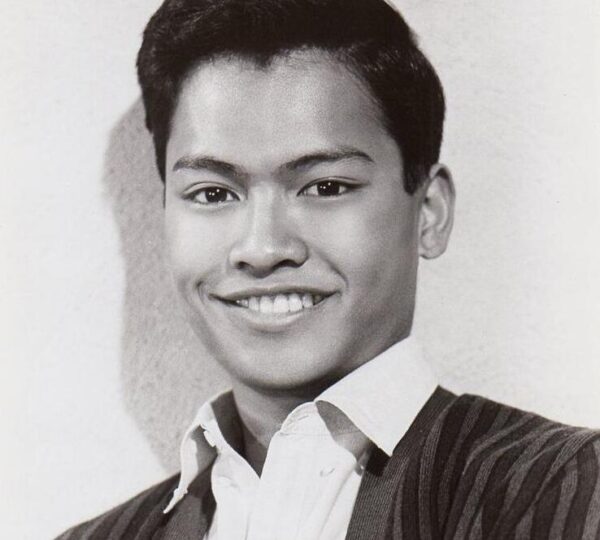

The face was familiar to millions; the name was often forgotten. When Patrick died on April 15, 2025, at the age of 82, many remembered the roles he played — but few fully grasped the remarkable journey that brought a war‑scarred boy from Manila to the stages and screens of America.

He moved through history like a ghost in plain sight: a Filipino boy shaped by war and loss, stepping onto American stages that were never fully built for him, performing in films and television shows at a time when roles for Asian actors were scarce, stereotyped, or marginal at best.

Adiarte didn’t burst through the door of opportunity so much as he inhabited the space between acceptance and exclusion — steady, unblinking, insisting with his presence that someone like him belonged in those worlds.

A Childhood Marked by Conflict and Survival

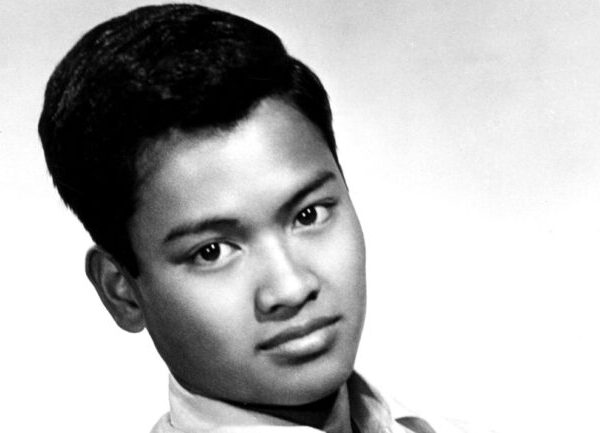

Patrick Robert Adiarte was born on August 2, 1942, in Manila, Philippines — in the midst of the Second World War.

His early life was brutally shaped by global conflict. In 1945, as a toddler, he, his sister Irene, and their mother, Purita, were imprisoned by Japanese forces on the island of Cebu.

Japanese occupation in the Philippines was ruthless; civilians were detained, many tortured or forced into labor, and families lived under constant threat.

Tragically, in the midst of this brutality, Patrick’s father — a captain with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — was killed just a month after their capture.

The horror of those years cannot be overstated: young children living amidst violence, displacement, and loss.

Patrick and his sister were reportedly burned during an escape attempt from their holding.

After liberation, the family made the difficult decision to leave the Philippines for the United States, arriving in New York City in 1946 via Ellis Island.

Finding His Footing on Broadway

Once in the United States, Patrick found refuge and expression in the performing arts.

At age 10, he joined the Broadway production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I — first as one of the royal children, then later as Prince Chulalongkorn.

This musical, a defining work of American theater, offered rare visibility for Asian characters, and young Patrick stood alongside legendary co‑stars like Yul Brynner and Gertrude Lawrence.

His Broadway work soon translated to film.

In 1956, he reprised his role of Prince Chulalongkorn in the Hollywood adaptation of The King and I, a major motion picture that brought Rodgers and Hammerstein’s celebrated work to a global audience.

Opportunities for Asian actors in Hollywood during the 1950s and 1960s were limited, often steeped in stereotype or exoticism.

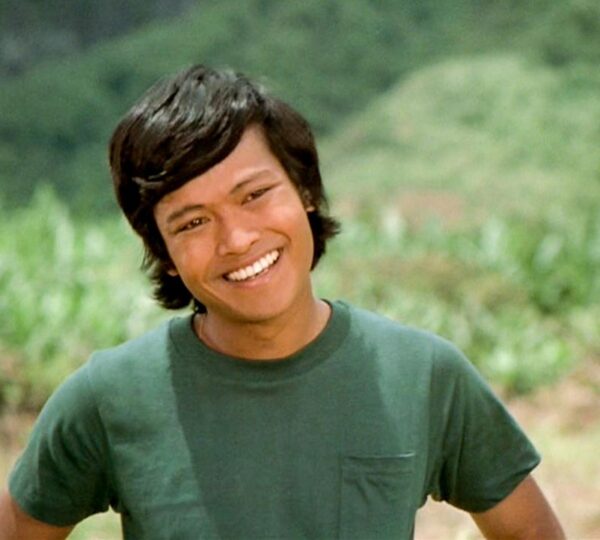

Yet Adiarte carved space for himself through talent and tenacity. Not long after The King and I, he was cast in Flower Drum Song — another Rodgers and Hammerstein musical.

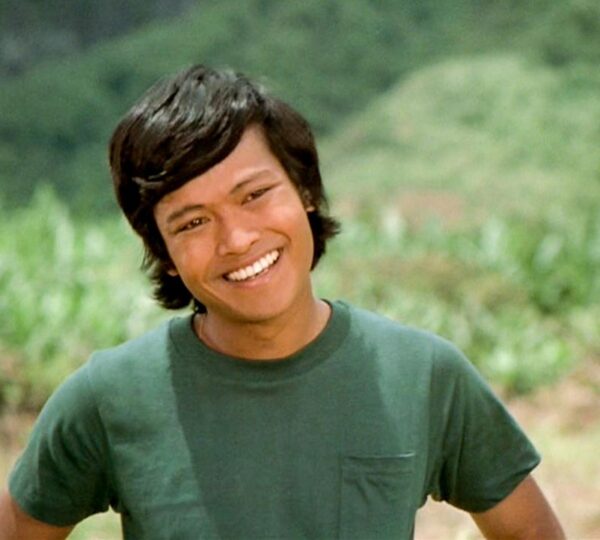

On Broadway, director–choreographer Gene Kelly saw in him a precision and spark that stood out even among seasoned performers.

In a memorable television appearance on Omnibus, Kelly mused that if there was another Fred Astaire in the younger generation, it might well be Patrick himself — a testament to his exceptional dance ability.

He went on to appear in the 1961 film version of Flower Drum Song as Wang San, further solidifying his presence in major Hollywood musicals — roles that would remain among his most recognized.

Navigating a Shifting Screen Career

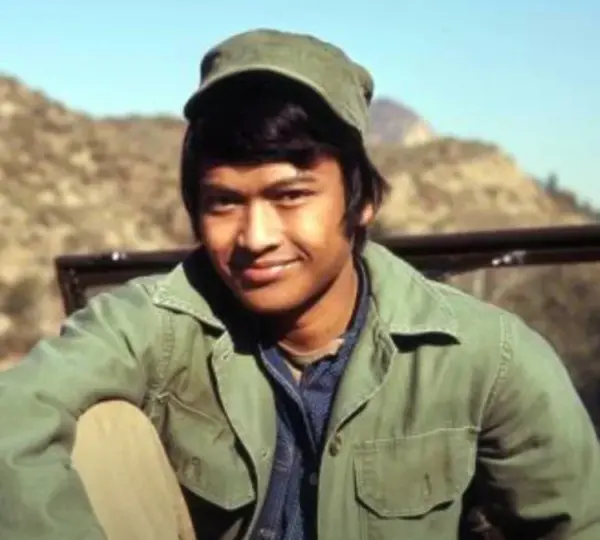

Beyond musicals, Adiarte’s screen journey reflected both his versatility and the limitations of his era.

In 1960, he appeared in the Blake Edwards comedy High Time, playing college student T.J. Padmanagham, and in 1965 he took on the role of Prince Ammud in John Goldfarb, Please Come Home! alongside Shirley MacLaine.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, he was a familiar face on television.

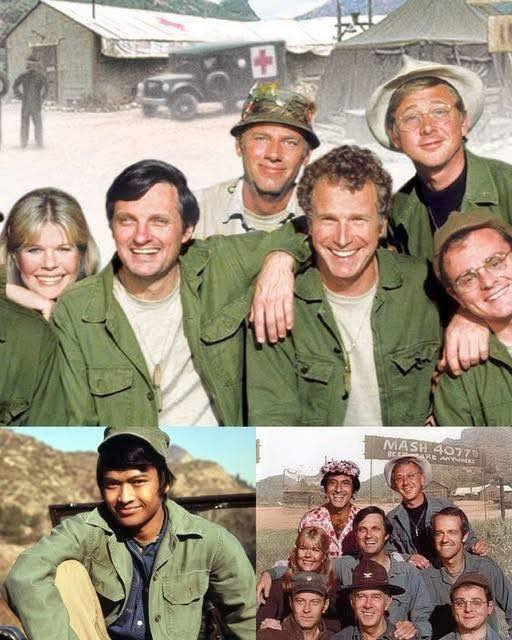

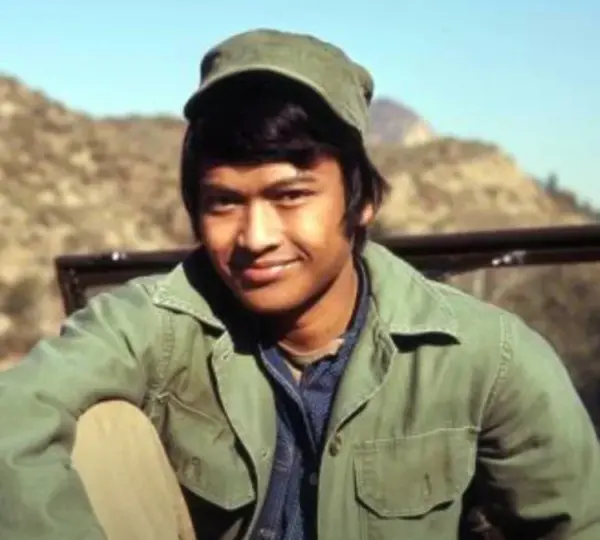

He appeared in episodes of popular series like Ironside, Bonanza, Hawaii Five‑O, and Kojak. But it was his television work on The Brady Bunch and, most notably, MASH* that brought him the widest audience recognition.

In The Brady Bunch’s 1972 Hawaii episodes, he played a construction helper who guides the family amid chaos; in MASH*, he brought warmth and earnestness to Ho‑Jon, the Korean houseboy assisting Hawkeye Pierce and Trapper John in several early episodes.

That role, appearing in seven episodes, resonated with viewers and remains one of his best‑remembered television characters.

Yet even success could be bittersweet. Hollywood in those decades often offered roles to Asian or Asian‑American actors that were limited by stereotypes or defined by their “foreignness,” rather than their full humanity.

Adiarte navigated this terrain with grace — bringing depth and dignity to every character he played, even when the industry failed to fully appreciate the breadth of his talent.

Retreat and Renewal: The Teacher Behind the Curtain

By the mid‑1970s, Patrick Adiarte had largely stepped back from mainstream acting. His final scripted television appearance was on Kojak in 1974, closing a screen career that had spanned nearly two decades.

Instead of chasing fading applause or struggling for ever‑scarcer roles, he turned inward, into another profound calling: dance instruction.

For many years, Adiarte taught dance — sharing not only technique, but also discipline, passion, and the empathy borne from a lifetime in performance.

He taught at institutions including Santa Monica College, shaping generations of dancers with a focus on rigour, presence, and expressive authenticity.

To his students, he offered what Hollywood sometimes could not: real recognition of their potential, thoughtful mentorship, and a grounding in the craft that transcended fame.

In classrooms and studios, his influence was quiet but profound — a legacy carried forward in every student who learned to move with intention and heart.

This was a different kind of spotlight, one that honored effort over image and growth over applause.

Beyond the Stage: Life, Love, and Legacy

Patrick’s personal life was as rich and layered as his career. In 1975, he married singer and actress Loni Ackerman, with whom he shared 17 years of life and creative exchange before their divorce in 1992.

Though they did not have children, those years reflected the artistic community in which he lived — interwoven with collaborators, performers, and friends who saw him not just as an actor, but as a creative force and a generous spirit.

Offstage, colleagues and friends remembered him as a thoughtful, warm individual — a mentor, gardener, advocate for Asian‑American performers, and a figure of empathy in an industry that all too often values surface over substance.

In later years, he supported organizations and voices striving for greater representation in the arts, aware that his own journey was part of a larger story of inclusion and recognition.

And yet, despite his achievements, Patrick remained something of an unsung figure — a reminder that many contributors to culture shape it without ever becoming headline names.

He was the face millions recognized, the actor whose performances stayed with people long after the credits rolled, and the teacher whose lessons echoed in future generations of dancers and actors.

An Enduring Echo

When Patrick Adiarte passed away from complications of pneumonia on April 15, 2025, in Los Angeles, he was surrounded by family who remembered him not only for his roles, but for his resilience, generosity, and humanity.

He was 82 years old.

Patrick’s name may fade from popular memory more quickly than his contributions deserve.

But his impact — on stage, on screen, and in studios where he taught countless young performers — will not.

His life tells a story of quiet defiance: of a boy shaped by conflict who stepped into spaces that did not always welcome him, and who stayed there with dignity.

It is the story of someone who understood that presence matters — not just the moment you appear, but the legacy you leave behind in the hearts and talents of others.

In the end, Patrick Adiarte’s story is not simply one of survival, or of fleeting fame.

It is the tale of a life devoted to art, resilience in the face of barriers, and service to future generations.

He may not have chased the echo of applause — but his work will continue to resonate in every performer who traces their first steps to his teachings, and in every viewer who smiled, remembered, or felt seen because of him.

Fame never saved him. It never protected him.

In many ways, it haunted him — or, at least, it echoed across decades of a life spent walking the razor’s edge between visibility and obscurity.

But the quiet truth about Patrick Robert Adiarte is that he made a mark deeper than most would ever know, even if his name was not always on the marquee.

The face was familiar to millions; the name was often forgotten. When Patrick died on April 15, 2025, at the age of 82, many remembered the roles he played — but few fully grasped the remarkable journey that brought a war‑scarred boy from Manila to the stages and screens of America.

He moved through history like a ghost in plain sight: a Filipino boy shaped by war and loss, stepping onto American stages that were never fully built for him, performing in films and television shows at a time when roles for Asian actors were scarce, stereotyped, or marginal at best.

Adiarte didn’t burst through the door of opportunity so much as he inhabited the space between acceptance and exclusion — steady, unblinking, insisting with his presence that someone like him belonged in those worlds.

A Childhood Marked by Conflict and Survival

Patrick Robert Adiarte was born on August 2, 1942, in Manila, Philippines — in the midst of the Second World War.

His early life was brutally shaped by global conflict. In 1945, as a toddler, he, his sister Irene, and their mother, Purita, were imprisoned by Japanese forces on the island of Cebu.

Japanese occupation in the Philippines was ruthless; civilians were detained, many tortured or forced into labor, and families lived under constant threat.

Tragically, in the midst of this brutality, Patrick’s father — a captain with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — was killed just a month after their capture.

The horror of those years cannot be overstated: young children living amidst violence, displacement, and loss.

Patrick and his sister were reportedly burned during an escape attempt from their holding.

After liberation, the family made the difficult decision to leave the Philippines for the United States, arriving in New York City in 1946 via Ellis Island.

Finding His Footing on Broadway

Once in the United States, Patrick found refuge and expression in the performing arts.

At age 10, he joined the Broadway production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I — first as one of the royal children, then later as Prince Chulalongkorn.

This musical, a defining work of American theater, offered rare visibility for Asian characters, and young Patrick stood alongside legendary co‑stars like Yul Brynner and Gertrude Lawrence.

His Broadway work soon translated to film.

In 1956, he reprised his role of Prince Chulalongkorn in the Hollywood adaptation of The King and I, a major motion picture that brought Rodgers and Hammerstein’s celebrated work to a global audience.

Opportunities for Asian actors in Hollywood during the 1950s and 1960s were limited, often steeped in stereotype or exoticism.

Yet Adiarte carved space for himself through talent and tenacity. Not long after The King and I, he was cast in Flower Drum Song — another Rodgers and Hammerstein musical.

On Broadway, director–choreographer Gene Kelly saw in him a precision and spark that stood out even among seasoned performers.

In a memorable television appearance on Omnibus, Kelly mused that if there was another Fred Astaire in the younger generation, it might well be Patrick himself — a testament to his exceptional dance ability.

He went on to appear in the 1961 film version of Flower Drum Song as Wang San, further solidifying his presence in major Hollywood musicals — roles that would remain among his most recognized.

Navigating a Shifting Screen Career

Beyond musicals, Adiarte’s screen journey reflected both his versatility and the limitations of his era.

In 1960, he appeared in the Blake Edwards comedy High Time, playing college student T.J. Padmanagham, and in 1965 he took on the role of Prince Ammud in John Goldfarb, Please Come Home! alongside Shirley MacLaine.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, he was a familiar face on television.

He appeared in episodes of popular series like Ironside, Bonanza, Hawaii Five‑O, and Kojak. But it was his television work on The Brady Bunch and, most notably, MASH* that brought him the widest audience recognition.

In The Brady Bunch’s 1972 Hawaii episodes, he played a construction helper who guides the family amid chaos; in MASH*, he brought warmth and earnestness to Ho‑Jon, the Korean houseboy assisting Hawkeye Pierce and Trapper John in several early episodes.

That role, appearing in seven episodes, resonated with viewers and remains one of his best‑remembered television characters.

Yet even success could be bittersweet. Hollywood in those decades often offered roles to Asian or Asian‑American actors that were limited by stereotypes or defined by their “foreignness,” rather than their full humanity.

Adiarte navigated this terrain with grace — bringing depth and dignity to every character he played, even when the industry failed to fully appreciate the breadth of his talent.

Retreat and Renewal: The Teacher Behind the Curtain

By the mid‑1970s, Patrick Adiarte had largely stepped back from mainstream acting. His final scripted television appearance was on Kojak in 1974, closing a screen career that had spanned nearly two decades.

Instead of chasing fading applause or struggling for ever‑scarcer roles, he turned inward, into another profound calling: dance instruction.

For many years, Adiarte taught dance — sharing not only technique, but also discipline, passion, and the empathy borne from a lifetime in performance.

He taught at institutions including Santa Monica College, shaping generations of dancers with a focus on rigour, presence, and expressive authenticity.

To his students, he offered what Hollywood sometimes could not: real recognition of their potential, thoughtful mentorship, and a grounding in the craft that transcended fame.

In classrooms and studios, his influence was quiet but profound — a legacy carried forward in every student who learned to move with intention and heart.

This was a different kind of spotlight, one that honored effort over image and growth over applause.

Beyond the Stage: Life, Love, and Legacy

Patrick’s personal life was as rich and layered as his career. In 1975, he married singer and actress Loni Ackerman, with whom he shared 17 years of life and creative exchange before their divorce in 1992.

Though they did not have children, those years reflected the artistic community in which he lived — interwoven with collaborators, performers, and friends who saw him not just as an actor, but as a creative force and a generous spirit.

Offstage, colleagues and friends remembered him as a thoughtful, warm individual — a mentor, gardener, advocate for Asian‑American performers, and a figure of empathy in an industry that all too often values surface over substance.

In later years, he supported organizations and voices striving for greater representation in the arts, aware that his own journey was part of a larger story of inclusion and recognition.

And yet, despite his achievements, Patrick remained something of an unsung figure — a reminder that many contributors to culture shape it without ever becoming headline names.

He was the face millions recognized, the actor whose performances stayed with people long after the credits rolled, and the teacher whose lessons echoed in future generations of dancers and actors.

An Enduring Echo

When Patrick Adiarte passed away from complications of pneumonia on April 15, 2025, in Los Angeles, he was surrounded by family who remembered him not only for his roles, but for his resilience, generosity, and humanity.

He was 82 years old.

Patrick’s name may fade from popular memory more quickly than his contributions deserve.

But his impact — on stage, on screen, and in studios where he taught countless young performers — will not.

His life tells a story of quiet defiance: of a boy shaped by conflict who stepped into spaces that did not always welcome him, and who stayed there with dignity.

It is the story of someone who understood that presence matters — not just the moment you appear, but the legacy you leave behind in the hearts and talents of others.

In the end, Patrick Adiarte’s story is not simply one of survival, or of fleeting fame.

It is the tale of a life devoted to art, resilience in the face of barriers, and service to future generations.

He may not have chased the echo of applause — but his work will continue to resonate in every performer who traces their first steps to his teachings, and in every viewer who smiled, remembered, or felt seen because of him.