According to the reporting shared by the family and those close to them, they believed Joshua would survive.

They believed the doctors would do what doctors do, that youth would matter, that prayers would land somewhere and be answered.

In hospital waiting rooms, time becomes a cruel trick.

Minutes stretch into hours.

Every door opening feels like judgment.

Every sound—the squeak of shoes, the murmur of staff, the distant beep of a monitor—feels like it might be the moment life changes forever.

Someone called the family.

Someone drove too fast.

Someone held a phone with shaking fingers, hoping for the right words and getting only fragments.

In families, roles appear instinctively in emergencies: one person becomes the communicator, one person becomes the quiet one, one becomes the one who keeps saying, “He’s going to be okay,” as if repetition can force reality into shape.

But reality does not always bend.

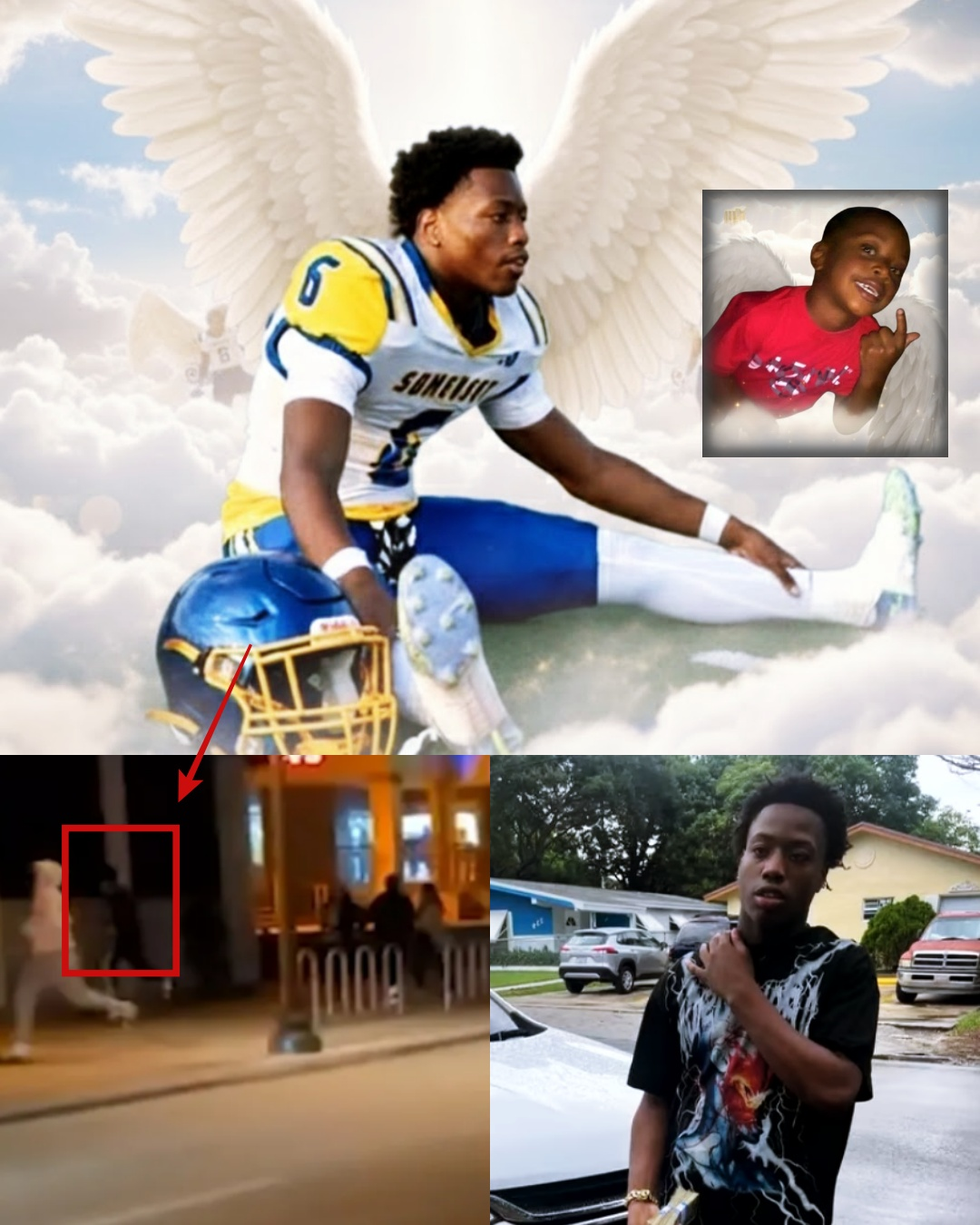

Joshua Gipson, Jr. died after being taken to the hospital, his family said.

Seventeen years collapsed into a single headline.

A future that had been detailed with hopes—Virginia Tech, graduation, adulthood—was suddenly reduced to grief.

And the year turned.

Midnight arrived anyway.

It arrived for strangers raising plastic cups and cheering under fireworks, for couples kissing, for friends shouting “Happy New Year!” into the salt air.

It arrived in bright colors over the ocean and exploded across the sky, indifferent to the boy who would never see it.

Somewhere close by, a family stepped into a new year without their child.

A mother stepped into January with a wound that would never close.

A community stepped into 2026 carrying a name it should not have had to learn this way.

He was only seventeen.

He was only there to celebrate.

And then he was gone.

A family friend, speaking to WPLG, tried to give words to what cannot be properly spoken.

“I feel like I just lost a child, and he wasn’t even my child,” she said.

Grief does that—it spills over boundaries, makes unrelated hearts ache, turns strangers into mourners because the loss feels too unfair to stay contained.

She described Joshua as warm, bright, good.

Not perfect—teenagers never are—but good in the way people mean when they say it with tears.

The kind of kid you trust around younger children.

The kind of kid who remembers to text back.

The kind of kid who makes adults believe the next generation might be kinder than the last.

She also spoke of his mother’s pain, saying the woman was “incredibly distraught” and “speechless.”

That word—speechless—may be the most accurate in tragedies like this.

Because language was built for ordinary days.

It was built for schedules and jokes and arguments and apologies.

It was not built to hold the moment a parent learns the world has taken their child.

In the hours after a shooting, people always search for logic like it might be hiding in the sand.

Why there.

Why then.

Why him.

Sometimes the answers are procedural—investigations, suspects, evidence, charges.

And those things matter, because accountability matters, because communities need to know the truth.

But for the family, for the friends who watched, for the people who loved Joshua, the question that remains is simpler and heavier:

How can someone die for nothing?

A witness told WPLG that Joshua appeared to be hit by a stray bullet in an exchange of gunfire between two people.

The phrase “stray bullet” sounds almost accidental, almost like an unfortunate detail of physics.

But there is nothing accidental about choosing to fire a gun in a crowd.

There is nothing accidental about letting anger become a weapon and then being surprised when an innocent person pays the price.

That is the quiet horror of public violence: it does not only harm the intended target.

It poisons the air around it.

It turns an entire street into a place people will always remember with a flinch.

It transforms the most ordinary acts—walking, laughing, standing near friends—into risks no one agreed to take.

On January 1, as the news moved through the city, people who had been on that beach began replaying their own choices.

If I had left earlier.

If I had walked on the other side of the street.

If we had gone somewhere else.

If I had told him not to go.

Survivors carry guilt even when there is no rational reason for it.

Friends who were with Joshua may spend years trying to understand how they walked away and he did not.

Teenagers, especially, can feel the weight of tragedy in ways adults underestimate—quiet nightmares, sudden anxiety in crowds, the way fireworks might never sound the same again.

And then there is the family’s grief, which has its own geography.

It spreads through bedrooms and closets and school hallways and the small places where reminders hide.

A hoodie on a chair.

A half-used bottle of cologne.

A text thread that will never update.

People will say, “He’s in a better place,” because people say that when they are helpless.

People will say, “Everything happens for a reason,” because people want the world to be orderly.

But sometimes grief refuses those comforts, because what happened has no reason that can justify it. Continue reading…